This interview continues my Soy/Somos conversations with people in the U.S. rooted in more than one culture. As a naturalized American citizen, I want to understand pieces of the mosaic that make up this nation. In today’s climate, these conversations feel essential.

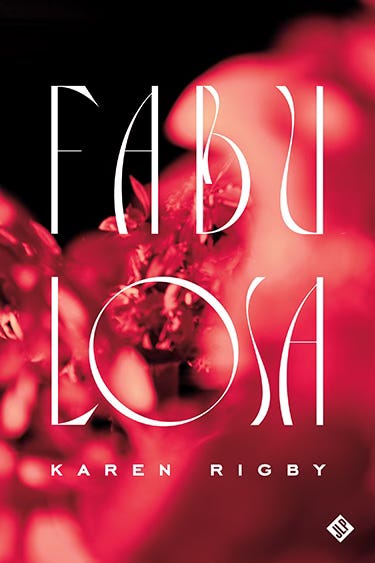

Born in the Republic of Panama in 1979, Karen Rigby now lives and writes in Arizona. Her latest poetry book is Fabulosa (JackLeg Press, 2024.) Her debut poetry book, Chinoiserie (Ahsahta Press, 2012), won the 2011 Sawtooth Poetry Prize. Karen is a National Endowment for the Arts literature fellow.

Karen, thank you for reaching out to me. I'm so pleased to have this opportunity to speak with you about your new book of poetry, Fabulosa, and to meet you—born and raised in Panama, as I was.

Would you tell us a little about your background?

I was raised in El Dorado, in the Bethania neighborhood of Panama City. I went to schools in the Canal Zone, schools that were known then as Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS), for the American military. Those schools also served the children of civilians who worked for the Panama Canal. All my schooling was in English.

My father was a security guard at the Panama Canal locks. So was my grandfather, who was born in Pennsylvania. My dad's mother was from the small island of Taboga in Panama, so my dad is both American and Panamanian. My mother is Chinese, born in Hong Kong.

What a heady mix! What languages did you speak with your mother?

Though my mother speaks Cantonese, I never learned it. She had studied in Hong Kong, so she is fully fluent in English, and we spoke it at home. Sometimes she would use Spanish and English, and it would become Spanglish.

My own favorite. Spanglish blends the staccato feeling of English, the one-syllable words, with the multiple-syllable grace of Spanish. And the speaker gets to pick and choose the mix, improvised on the spot like jazz.

What drew you to poetry?

I always loved reading. I'd be at the Fort Clayton library all the time. That's where I first encountered American poets—Sharon Olds, Rita Dove, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, whatever they had available. In middle school, I became interested in writing my own work. Of course, it was amateurish then, but I was hooked. I left Panama for college and majored in Creative Writing at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, then went to get an MFA in poetry at the University of Minnesota.

You were rooted in at least three societies and raised in a tropical nation. How did this contribute to your poetry?

Panama is such a lush place. Everything is alive, organic, and complicated. The influence is more oblique and indirect: I am particular about images, making sure the writing is vivid, with multiple layers of darkness and light. If I'd grown up somewhere else, I'd be writing differently.

Does Spanish influence your poetry? Does the language itself offer something?

In English I have more idioms and metaphors. I can say the same thing in more than one way. In Spanish I only have one way. So, if I use Spanish in poetry, it's occasional. I have to think in an entirely different way.

Something that I've found affects flexibility in language, particularly as a life calling, is reading great amounts—what other writers have said and how they've said it. This is how my English has deepened.

What are you seduced by when you begin a poem?

Usually it is a word, or a first line. Or an image. Once it appears in my mind, I try to see what more can be pulled out of that. There's this one poem about a tangelo. I wasn't intending to talk about the 1989 invasion in Panama, but when I started describing how insignificant a tangelo can feel—while still being very tactile—suddenly it connected me to that whole other topic and era.

What do you do when you feel a little dry in terms of writing, or lose a little faith...?

I always come back to reading my favorite collections. There's Diane Seuss, Angie Estes, too many to name. I'll reread other people's poems to see what they are doing, to find an image, a word. Being absorbed in that kind of language and paying attention to it helps me return to my own work.

There's a beautiful strangeness in Diane Seuss' work that reminds me of your work, a profusion of images. Your poems are both lush and restrained, these two impulses knocking against each other.

While I was waiting to chat with you this morning. I was reading Seuss' Still Life. She writes so much about paintings. That really fascinates me.

I notice that you have several ekphrastic poems in Fabulosa. Chagall's “Chrysanthemums" is one. You are attracted to beautiful things, to glamour. Knowing that glamour pulls at you must be comforting—there's going to be another image you can depend on to pull you in. No?

Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that I am always attracted to the arts, all the arts, including such things as figure skating and television dramas. It's a reliable source of inspiration. But I'm also conscious that I don't want to repeat myself. I don't want the ekphrastic to become a habit or expectation. I need surprises to keep myself interested.

The first, dazzling poem in Fabulosa is titled “Why My Poems Arrive Wearing Black Gloves.” Do you have a background in fashion? After reading these poems I feel there's got to be a "she wanted to be a designer" some time in your life.

As a little girl I would draw, though not very well. My mother used to sew her own dresses. I don't have that.

But, black gloves, the drama of that, was it something that you wanted?

I think for me it's a persona to play with. Poetry allows the poet to experiment with different voices, tones, attitudes and topics.

While every poem contains a facet of me, as its creator, every poem also presents the opportunity for a more expansive and sometimes heightened view. I find it fascinating to explore the multiple versions of a life. As for the gloves, I have a fondness for certain classic movies.

What was the last wonderful book that you read?

It's right here at my desk. The poetry of Virginia Konchan in Bel Canto. Her work is so intelligent that I almost can't grasp it.

Panama is a wildly diverse place, almost more diverse than the United States. The communities seem to interact easily. I wonder if you have any feelings about growing up in that environment and what seems to be happening here now as regards new immigrants.

Growing up in Panama City was like growing up in a small town. It felt like everyone knew everyone. I had a large extended family. I went to school with Americans. You are right that there was a certain kind of inclusivity, because we didn't think twice about what someone was or where they were from.

When I moved here, it felt completely different. Not about immigration or not immigration, but now I was anonymous. You could almost get lost. Everyone in their own suburb. It's not the same feeling that Panama has. Without wanting to make a big commentary, it does feel more closed off here. Isolated. Everyone keeps to themselves.

In the United States you can be a chameleon—depending on the context—and it tends to change. It's that quality of being able to be many things at once and yet not at the same time.

That's as good as I've heard about living-in-between. André Aciman, author of Roman Year, says something seemingly simple—so appropriate—about immigrants: "Living in between is the American Condition." It takes a while to be comfortable in this kind of space. To be who you are and to steal from wherever you are.

Are you starting to gather new poems... working on something specific?

Slowly. I have the idea in mind to write a book of poems relating to Panama, but I'm finding it difficult. I know that for this one I can't rely on my memory alone. It would be new territory for me. My family moved to Florida when I left for college. They'd retired. The Panama Canal would revert to Panama on December 31, 1999. I haven't been back there since I left.

I'll meet you there. A visit would trigger the jungle, the fences of dry logs in the countryside that begin sprouting. You would not recognize the country—the modern canyons 60 stories high, the new neighborhoods, hospitals, highways, the rapid pace. Complicated.

I noticed that you are doing a reading of your poetry and craft conversation on February 20th with the Writer’s Center. Here's the link for others. It's free. I'll be there listening. I'll wave at you with my little emoji hand.

I’ll wave back, Marlena.

It’s been a privilege to hear your story and thoughts about the work of poetry. Thank you for letting us share this poem from Fabulosa. (JackLeg Press 2024), first published in FIELD.

(Reader - The poem’s line breaks and stanzas will be affected when viewed on cell phones. For the correct view, please access the poem on your computer screen)

On Marion Cotillard’s 2008 Oscar Dress

Glamour is a mermaid silhouette: Jean Paul Gaultier

in scalloped lines, X-back sweeping to a fishtail hem.

Never mind white like wedding cake piping or fit

like second skin. What I love about sleeveless

couture is negative space:

collarbone, shoulders, neck

fugitive as the first crocus. The dress stops

everyone on the red carpet—including me,

the viewer at home—

a silk aerialist

spiraling onto the stage. It’s that color of palladium,

the exact moment thread galvanizes

air. The day I watch you playing Édith Piaf

I understand the brute song housed

in the chest finds a way out.

What’s in a dress? Stitch. Scaffold. Silver edge.

A piano hammering notes pure as jet.

The best dress I ever wore was forest green velvet

tapered to a bee’s waist. The skirt hung like a bell.

Glamour is muscle made movement. A body turned salt.

Dear Readers, I hope you found this conversation with Karen Rigby illuminating. Please show the love by checking the heart and leaving a comment.

What here moves you? As you know, this is a conversation.

Fascinating to hear about the truly multicultural experience of Panama, and to read this lovely poem. ❤️

What a great interview - and such beautiful writing -

"The best dress I ever wore was forest green velvet

tapered to a bee’s waist."