Soy/Somos: Dr. David Gomez

You are going to have to work very hard to fail, because I am not going to let you fail.

This interview continues my Soy/Somos conversations with Latinos and others in the U.S. rooted in more than one culture. As a naturalized American citizen of many decades, I fell into this naturally, wanting to understand pieces of the mosaic that make up this nation. In today's climate, these conversations feel essential.

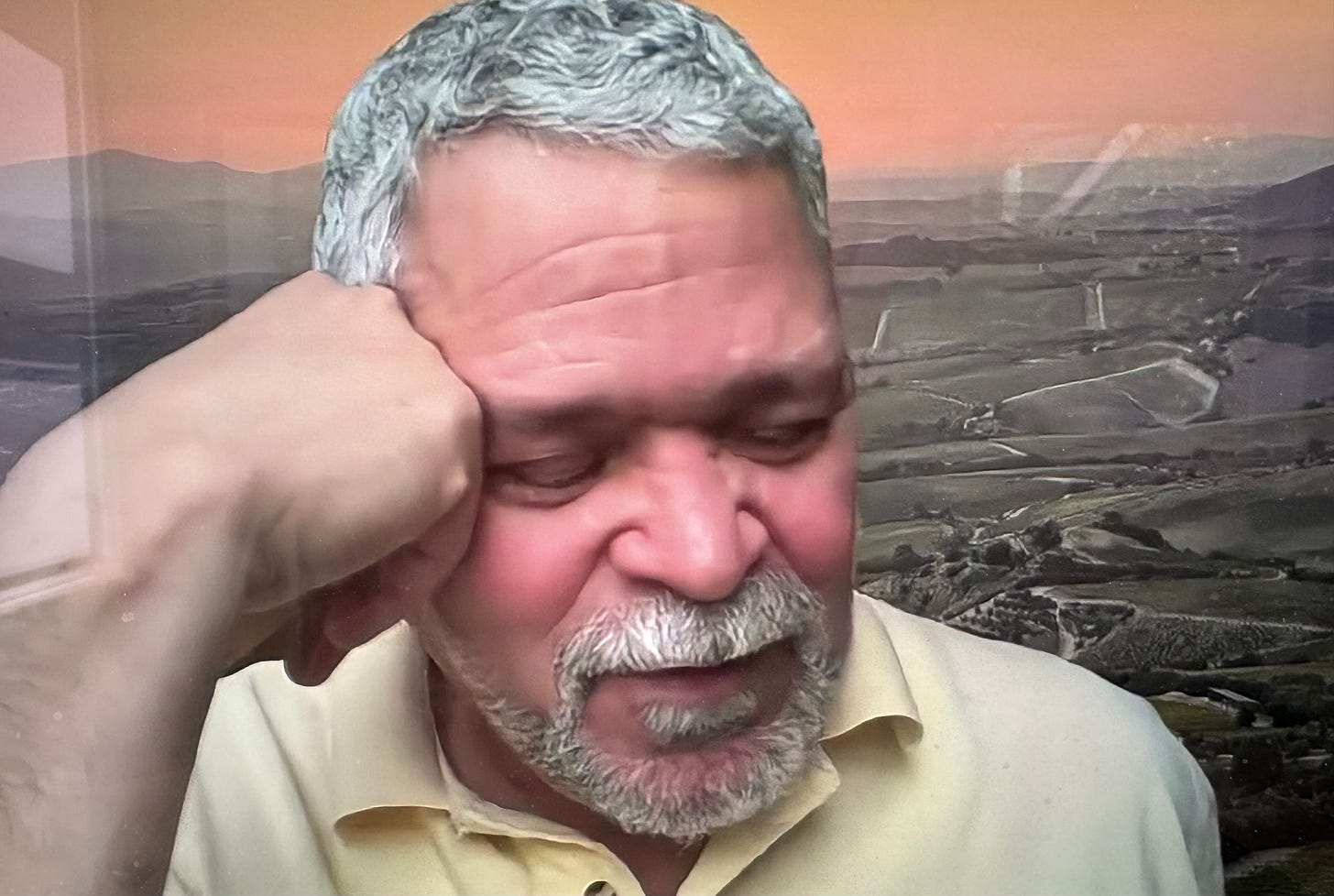

A week ago I interviewed Dr. David Gomez, former president of Hostos Community College in the South Bronx, a leader in education, Puerto Rican, born and raised in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the '50s and '60s

For several weeks I'd been finding myself muddled, wanting to share with you travel experiences in Oaxaca, Mexico, trying to sort out what it means to be a tourist today. The conversation with Dr. Gomez righted my head. I am reminded again of what it means to listen closely to individuals who have different life experiences from my own. I can try to get under the skin of someone else and begin, just begin, to piece together new understandings.

Dr. Gomez and I spoke about his young life in the Lower East Side of New York--where so many immigrants first set foot in the United States—and the influences that pulled him toward a 47-year career in education, his long experience with the community college movement and its essential mission in American society.

This conversation is of one piece, and I will share it with you whole. It deepened my own understanding of the American nation I am a part of. I hope it will also enrich your life.

"Immigrant groups settle where they can keep their families reasonably safe."Dr. Gomez. it's such a pleasure to meet you, on screen, that is. I've heard so much about you from our mutual friend, Kevin, who first met you when you were a boy and he was director of a youth program in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Please call me David, Marlena.

David, mucho gusto. Tell me, who was the boy growing up in the Lower East Side? Who was your mom? And your dad?

My parents were campesinos, peasant farmers in Puerto Rico. Neither of them had schooling beyond the fifth grade. They came to the United States after World War II, a time of one of the large Puerto Rican migrations to the mainland. The men came first, established a footing, and gradually brought over their families.

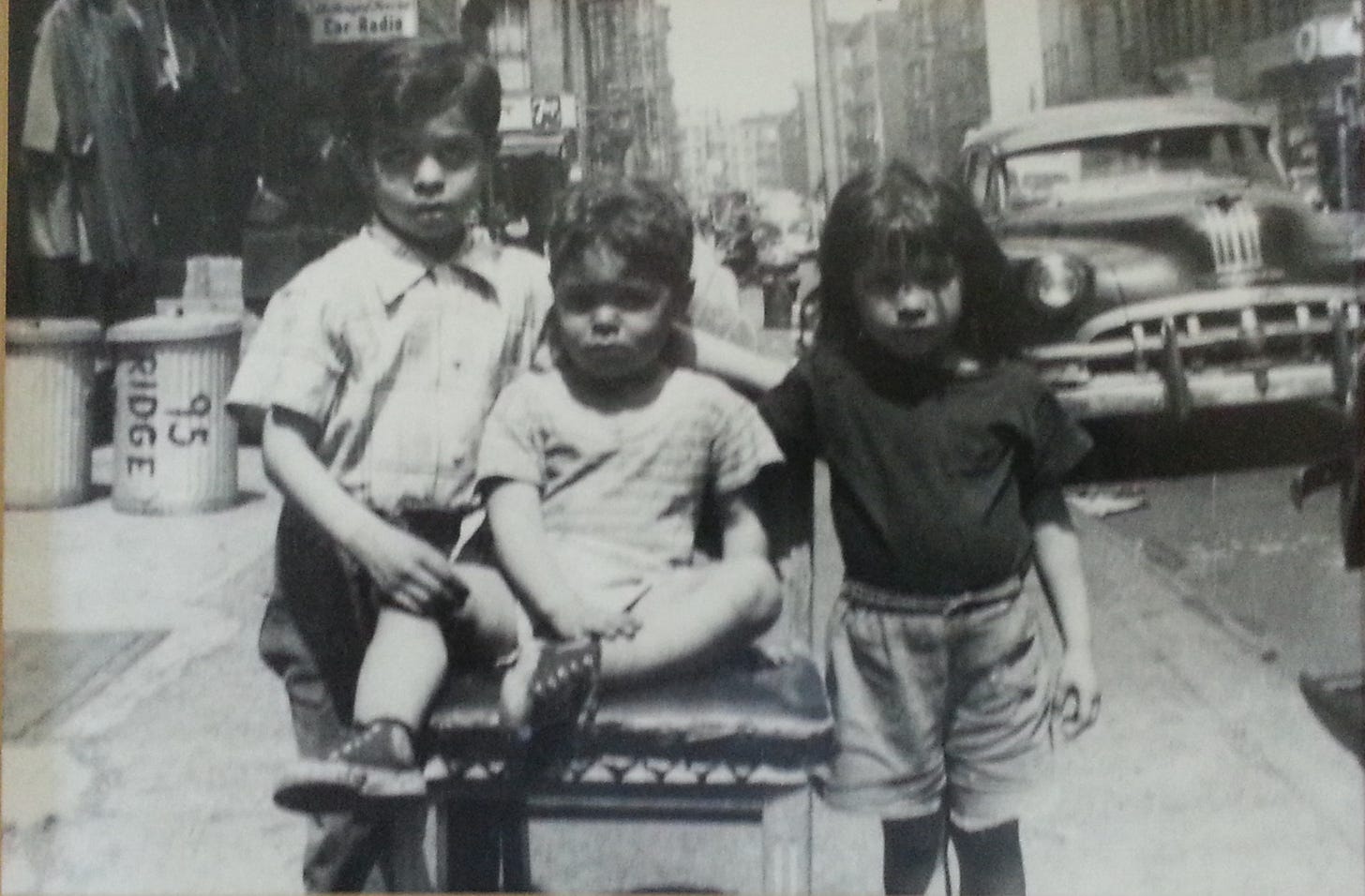

My mother and the first four of my siblings arrived in 1948. My sister Ida, me, and my younger brother were born here in the United States. The healthcare in Puerto Rico then was very poor, and an older sister had died in childhood before she was two. I believe this is one of the reasons my parents left Puerto Rico. Like generations before them, they settled in the Lower East Side--as had the Irish, the Jews, and the Italians.

What do you remember, David?

In the '50s, during my childhood, the Lower East Side was a beautiful mixture of races, cultures, religions. My mother spoke more Yiddish than English. This is before the bodegas took hold, because most of the small stores—general stores, butchers—were Jewish owned. We lived in two worlds. Spanish at home and English in the rest of the world. For my older brothers and sisters who were born in Puerto Rico it was a special struggle because they only began to learn English going into second, third and fourth grades.

We were obviously very poor, but it didn't feel like it because our family, my parents and seven kids, were and remain very close, so there was a lot of family engagement. Our extended family, aunts and uncles, cousins, and the church also played a critical role in our lives.

For me it was incredibly fun, sometimes scary, especially going into elementary school for the first time not speaking English, not understanding what was going on around me. In the public schools in those years—in the late 50s and early 60s—the philosophy was you're an American now. Speak English. There wasn't any encouragement of the spoken Spanish language, certainly not for the culture. So that was a little bit of a battle for us who were very proud Puerto Ricans. My father never used the term to his dying day of Hispanic or Latino. As to "Spanish," as they referred to us in the 50s, my father would say, tú no eres español. Eres puertoriqueño.

When I was teaching, I remember telling my students that the notion of Hispanic as a monolithic group is a total misconception. We don't identify ourselves that way. If you ask someone of Mexican heritage, they will say, soy mexicano. O dominicano. I am Cuban, Argentinian....

Soy panameña.

Sometimes I identify with the Winston Churchill quote about the English and the Americans, "We are two people divided by a common language."

The Spanish speaking communities in the Americas are so diverse culturally and racially, that for people to understand us requires that they approach it the same way as if they were looking at the Irish versus the English, versus the Australians, the Canadians, the Americans. They speak the same language, more or less, but they have different histories and cultures.

Some common threads are pretty strong: the weight of family, the Spanish language (with some exceptions), the responses in our countries to US intervention. Y más.

Yes, the commonalities are strong, but the differences are important.

Can you give me an example of ways Dominicans, for example, and Puerto Ricans are very different?

The Puerto Ricans have been living in the South Bronx in significant numbers since the 1930s and 1940s. The Dominican presence in the South Bronx really begins in the 1980s. There is a cultural conflict that I am also seeing in El Barrio, in Spanish Harlem, with the Mexican communities. It manifests itself in the food products that are carried in stores, whether or not you worship la Virgen del perpetuo socorro o la Virgen de Guadalupe. "Look, we were here first. This is our culture." The Puerto Ricans in the South Bronx have been very possessive, from musical genres, to cultural icons, to whose name is placed on certain street intersections.

The Dominican community (though I am not an expert on the Dominican community) having arrived during political conflict in the Dominican Republic are suspicious of government. "Everybody's corrupt, everybody's in it for something." The way we protect ourselves is by being heavily invested politically. Their investment in the economic and political fabric has been strategic and purposeful, which is not my experience with the Puerto Rican community.

Puerto Ricans engaged with American society differently. The racism in New York City, while it still exists, was much more overt in the 50s. I was literally told as a child, you people just don't have the talent for college. I don't think that kind of racism is prevalent now. I am not that naive to believe it's gone away, but the creation of bilingual programs, the role that ASPIRA played in the educational community, the movement of everybody, including the Young Lords in the 60s, to change the landscape in New York created a different foundation for groups that arrived after.

People identify the Puerto Ricans in Manhattan as living in El Barrio—114 Street, that kind of thing—near La Marqueta. Puerto Ricans actually have lived throughout the city wherever you can find a place to live affordably with your family. My family settled in the Lower East Side. Other families settled in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

Immigrant groups settle where they can keep their families reasonably safe. When you can't, you pack up and move somewhere else.

This reminds me, David, what was your home like growing up in the Lower East Side?

When my parents first moved to the Lower East Side we lived in the tenements. Ours was on Ridge Street between Delancey and Rivington. Our apartment had two bedrooms and a common room that we used as a dining room. The bathtub was in the kitchen. There was one bathroom in the middle of the floor that all families living on a floor shared. My parents lived there from 1948 to 1955.

We were like the Jeffersons, "moving on up." I was three years old when we moved to the housing projects. We had three tiny bedrooms, a bathroom in the apartment with the tub and commode separate, so you had some privacy. And my God, a living room! We thought we had inherited a fortune! It was very modest, a NYC housing project built as part of the WPA just before World War II.

For most of my youthful existence, up until the time I got married, even a year or two after, I lived within a ten-block radius of St. Mary's church on the Lower East Side. That was my life. And that was everybody's life as well.

Dr. David Gomez has dedicated five decades of his life to education in different senior roles at the City University of New York, serving as President of Hostos Community College in the South Bronx from 2014, before retiring in2020. He attended New York City public schools, holds a BA in English Literature from the State University of New York at Albany, and both a master's and doctoral degree from Teachers College at Columbia University.

"Go to a commercial school"David, why Education? What was going on in the mind of the 7, 12, 15-year-old boy that led you there?

For a lot of immigrant groups, the only professionals they interact with are teachers; well, teachers and priests. So, in terms of role models, the people available to me were teachers. I was not exposed to investment bankers, for example, people who looked at finance as a profession. In fact, "it's not a real job...you don't do anything..." so little did I know.

The pivotal moment was when I had a junior high school English teacher whom everyone called Mr. Geemenez. The first Latino teacher I had ever seen, let alone, had.… The first thing Mr. Jimenez did in class was take us on a road trip to Connecticut to see Hamlet. I was mesmerized. I had never experienced a Shakespearean production live on stage. To hear Mr. Jimenez expose us to English poetry, English literature, and the language, these were shocking experiences and things I was told were not for me. Hey, this is something I would like to do for other people, for young students in disadvantaged communities.

I began to see that I could perform as effectively in what to me was a foreign language as I could in my native tongue.

When I was looking into high schools, I was told, "Don't bother going into an academic school, because you're never going to get into college. Go to a commercial school." In fact it was Mr. Jimenez who said to me, go into an academic program.

In those days schools directed you where they wanted you to go. I ended up in Central Commercial High School because that's what where we were told we needed to do. And, you know, I did quite well there....

This is where I met my second teacher of color, an African-American teacher, Mr. Lovell, who in my Junior year of high looked at me in the eye and asked, Mr. Gomez, where are you going to college? Well, I said, my family can't afford to pay for college, and I don't know if I can get in. Mr. Lovell stopped me in mid-sentence, Mr. Gomez, you are not listening to me. I asked you where? I was taken aback. He literally hounded me. It turns out he also requested me for his senior year history class. By that point, I began to think that college might be an option for me.

In those days, our good friend Kevin was coach for basketball and he'd found a new educational opportunity program at the State University of New York at Albany. He gathered a group of us and said, guys I have these applications. But, we said, we can't afford to go to school, or to live on campus. Boys you don't understand, this is different.

There we were on the gym floor with these forms, trying to figure them out. There must have been 30 or 40 of us in the initial group. Some walked away and didn't take advantage. The Lower East Side was a very tough place then.

We came up with one cohort for 1969. I was in the 1970 cohort. Kevin helped usher us through.

It was an interesting confluence of factors: teachers and mentors who were encouraging us to go to college. Then Kevin finding a mechanism that would allow us to do it. Without this, I would have been forced to do what my other siblings did, which was to go to college at night, work during the day. I was talking to my sisters recently. We all graduated in reverse chronological order because I—almost the baby—was the only one with the opportunity to go full time. People spent a great deal of time investing in me. I am very grateful.

"being in the room when it happened"David, the larger question I want to address has to do with community colleges, how they work, how they can help young people today. But—first—I have a burning question about the much celebrated Teachers College at Columbia University--whether in the Masters or Doctorate. What was the best thing about Teachers College?

I was lucky when I got there to study with some of the leaders in the higher education movement. Walter Sindlinger was my mentor and very active in the Truman Commission, which issued a report to President Harry Truman on the condition of higher education in the United States. The Truman Commission is credited with coining the term "community college." Before 1947 two-year colleges were known as junior colleges. The notion of a community college was something different in terms of its responsibility to the local community and to providing opportunities for those who could not afford it.

In those days if you went to a college other that City College, you had to commute or travel 75 miles and live on campus. The Truman Commission changed the landscape.

Walter Sindlinger, rest his soul, got me interested in community colleges. He was there when it happened. To coin a phrase from Lin-Manuel Miranda in Hamilton, "Being in the room when it happened."

All of my professors had been either college presidents or deans. They weren't just talking about something; they were sharing experiences. It was tremendously exciting. I picked people's minds and was incredibly obnoxious. They looked at me rather curiously but were entertained by my questions. In the mid 1970s there was a lot of energy. Education was still central to the agenda. In the political arena people were very much committed to educational opportunity.

I found myself swimming in these waters with people who were in my experience not only great scholars but leaders in a movement that was very important to me.

"For people of color, the modern community college is the primary gateway to higher education."I am not fully familiar with the mission of community colleges today, but I recognize their importance. Can you speak to this?

The Truman Commission report of 1947 is actually entitled, "Education for American Democracy." Although people cite it all the time, very few read it. I have. I own a copy of it. It's interesting the way the mission was framed in 1947. Among the things it said were:

a) that people should have access to education, a college in every community, so geography should not be a barrier.

b) that education within these institutions should be diverse, to include preparation for a transfer to a four-year institution as well as, when appropriate within a community, occupational preparation, such things as nursing, engineering. Auto mechanics might also be part of that.

For people of color, the modern community college is the primary gateway to higher education. There are more people of color in community colleges than there are in any other form of higher education combined. It's kind of odd to think that I was educationally privileged. I was a good student who got good grades and was able to go to top-flight public institutions. A lot of students I went to high school with were much brighter than me, but they were playing. They were doing things on the street that probably they should not have done. Given a second opportunity, they might have blossomed.

This is what community colleges do better than anything else. They provide students who do not fit the classic academic background—high SAT scores, A's and B's in high school, debate team, and so on—an opportunity to show their academic chops. What are they capable of? Often, they are intellectually more capable than people appreciate or realize.

Working with community colleges was a deliberate choice. I was offered deanships and presidencies in four-year institutions. I recognize that four-year institutions have wonderful leadership, people committed to that work. I love this work. If I could do it well, it would make a difference in people's lives.

To add to your earlier question of how community colleges work, for me it's the cross-generational impact, even when you don't know it at the time. I'll give you a concrete example. It's 2014, I am back as a college president at Hostos and having a conversation about Sonia Sotomayor coming to visit. "That's great! But why would a Supreme Court Justice want to visit, other than the fact that she's from the South Bronx?" And people said, don't you know? Her mother graduated from Hostos.

Celina Sotomayor, the Justice's mother is the kind of quintessential community college student. Single mom, working at a hospital as a nurse's aide by day, going to school at night for her nursing degree to provide a better opportunity for her children. The children went on to successful careers, the most notable, a sitting United States Supreme Court Justice.

That story cannot be told at Harvard or Yale. That story can only happen in community colleges, because people come in, and even if they themselves do not become Nobel prize winning laureates—and by the way, some of them do—or become doctors and lawyers--and many of them do--the generations that it impacts, shifting the economic paradigm away from poverty and dependency to inter-generational success is what makes it for me a critically important segment of education.

I hear students speaking in Spanish, in French creole, many of them with their own children in tow as they go to classes because they couldn't get a babysitter that day, and I think, oh my God, this is what my family was all about. They couldn't realize the dream themselves, so they let me do it.

People come to us with severe financial limitations, sometimes a history, whether it's a criminal history, an educational, or family history that might be viewed as debilitating. But they arrive in an environment where the attitude is, we can make it, and we can help you make it. I would tell my students, you are going to have to work really hard to fail because I am not going to let you fail.

"We have to figure out ways to ensure that our students are better prepared for the four-year institution."Would you help me understand how community colleges fit within CUNY, the City University of New York?

CUNY is a comprehensive university, the only one in the country made up of two-year, four-year, and graduate institutions. In all other systems in the country, community colleges are independent schools, or if they are part of a system, they are clearly separate and apart.

So with other community colleges not aligned with a city or state institution are costs vastly different for the student?

One of the good things about the community college system is the express intent to make it affordable. Wherever you are in the country, the cost of going to a community college is more driven by state funding. The funding model nationally is: one third of the costs come from tuition revenue, one third from the municipality, one third from the state. By and large, if you look at the costs of attending a two-year community college versus your freshman and sophomore years in any institution, public or private in the same region, it would be minimally one half to one third of the cost of attending a four-year institution.

What proportion of students enrolled in community colleges graduate?

This varies dramatically. The national on-time graduating rates unfortunately are abysmally low. I believe on average they are 17.5 percent. Originally at Hostos we began with an eight percent graduation rate. We got it up to twenty and are approaching thirty, which in New York City was virtually unheard of, the collective effort of the faculty making this a priority.

The things I try to explain is that very few people are able attend full time. People have to work even if they are receiving public assistance, just to survive. A student may start out full time because they need to go full time to get financial aid. Within a year, less than half are still attending full time. I believe this is true for most community colleges. It doesn't mean the students have left. They have kids to support. This is just to provide context. You have huge numbers of students who fall below the poverty line. Comparing that student, a 25-year-old single mom, to an 18-year-old kid going to Harvard or Columbia is absurd. You are not talking apples and oranges. These are apples and calabazas!

We must do a much better job in community colleges to encourage and support students to finish. At CUNY more than sixty percent of those graduating go on to four-year colleges. In fact, most of the enrollment at four-year colleges at CUNY are made up of students who graduated from community colleges. So the challenge is not graduating students, necessarily, but how to help them be successful in the four-year institution.

Community colleges have small class sizes—generally 24-27 students per class. Everyone has a counselor. There's an intimacy and a support network that while it needs to be improved is part of our DNA. The nurturing is critically important, but we have to figure out ways to ensure that our students are better prepared for the four-year institution.

We had an immigrant African student who graduated Hostos and went on to Harvard. Within a semester he was coming back. He was doing well academically but said, I don't belong here. It doesn't feel right to me. He was feeling challenged and wanted to drop out. We were all working with him. Stick it out. You can do it. And he did, thankfully, and he graduated. It took a lot of fortitude on his part.

"The liberal arts are a vital necessity."One last question for you, David. Is there room for a liberal arts education in the community college, given all the things the young people and the school system are facing?

It's not just room! It's a vital necessity. More than half of all the students who attend community colleges, sixty to seventy percent, are enrolled in a liberal arts program with the express intention of transferring to a four-year institution.

We are discovering in this country the lack of critical thinking. People look at the internet as authentic and legitimate sources of information as opposed to understanding how to analyze and confirm the authenticity of anything. I don't know of any community college in the country that doesn't have a liberal arts requirement, a minimum of one third of the credits in the liberal arts that I would fight to the death to protect.

So many of our students are students of color. You don't want to create a kind of caste system in higher education, that only the people who go to senior and four-year institutions are white and middle class. That's not the world in which I want to live or where I want my daughters or grandchildren to live.

There is a critical need to keep that opportunity open through the liberal arts, so our students can pursue positions of leadership. I am immensely proud that community colleges provide an opportunity for students to get into higher education. But the reality is that positions of leadership require baccalaureate and advanced degrees. If you want to become an MD, a college president, a bank president, that avenue should be available to you as well. Because the vast majority of students of color who attend higher education begin at community colleges, that opportunity has to be kept open and maximized.

Dear readers and friends, querido lector -

What questions did this conversation raise for you?

What answers did it provide?

As always, let me know what moves you.

Interesantísima y magnífica entrevista, te felicito!!

What a great interview! I have found these essays to be so enlightening, and tremendously enjoyable to read. Bravo to David Gomez! You have helped me to understand not only your moving and impressive background but also the importance of community colleges. I, too, attended Teachers College and found it to be a transformative experience. Marlena, keep going on these extraordinary interviews that are so beautifully written.